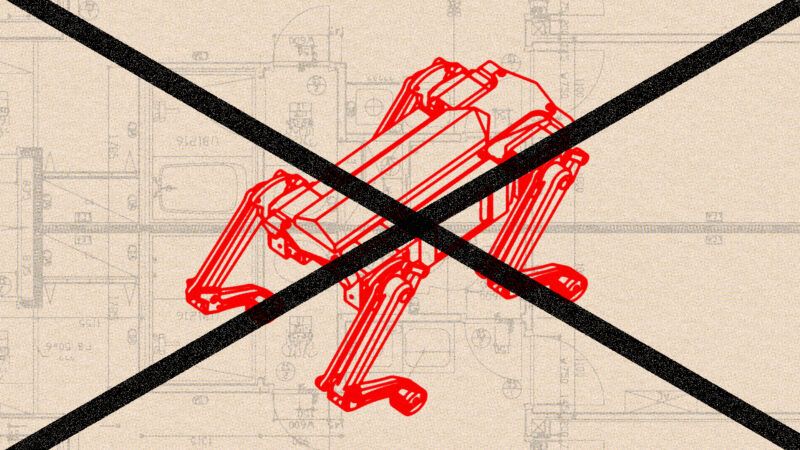

We Should All Be Nervous About Killer Police Robots

The San Francisco Police Department assured the public it had "no plans to arm robots with guns." But assurances aren't guarantees.

A week after voting to allow local law enforcement to equip robots with potentially deadly explosives, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors on Tuesday reversed course, nixing a policy proposal that would have permitted robot-delivered lethal force "when risk of loss of life to members of the public or officers is imminent and outweighs any other force option available."

The board backtracked from an initial 8–3 vote after noisy public outcry against "killer robots," with one supervisor, Gordon Mar, tweeting regret for his pro-robot vote because of "the clear and compelling civil liberties concerns." Initially, Mar said, he thought the proposal's guardrails were adequate, but he came to believe they were not. Moreover, he added, he doesn't think "removing the immediacy and humanity of taking a life and putting it behind a remote control is a reasonable step for a municipal police force."

That latter caution isn't as easily debated or quantified—it's more a squeamish instinct than a specific policy prescription like the call for guardrails. But both are needful as the technology available to the state for law enforcement and adjacent activities, chiefly surveillance, continues to rapidly advance. We need both concrete legal strictures and a general wariness of developments that automate, totalize, and dehumanize government processes in a manner that makes big policy reversals as well as individual recourse difficult to obtain.

The case for legal strictures is straightforward enough: Without them, mission creep is near inevitable. You start with a policy that seems very sensible and well-grounded in assurances of the care and humanity of those in charge. But you don't stay there. New uses come to mind, first similar enough to the original scheme and then increasingly distant. Frogs don't actually stay in the boiling pot, but people do.

SWAT teams are the obvious comparison here. They were created to address unusual, high-pressure situations, like the classic armed-bank-robber-with-hostages scenario. Now, fewer than one in 10 SWAT raids perform their original purpose. The rest—and there are more than 100 SWAT raids of private homes in America daily—take on far more mundane circumstances, many enforcing "laws against consensual crimes" like drug use and sales, as former Reason staffer Radley Balko has documented.

In San Francisco, after the first vote, the police department assured the public it had "no plans to arm robots with guns," in the phrase of the Associated Press. That's better than the alternative, but it isn't actually a guardrail. It isn't even a promise of a guardrail. It's a status update on conditions that—absent some constraint of law—are subject to change.

That kind of slippery language from officials on the verge of acquiring new power should always be a red flag, one on the scale car dealerships are wont to wave. It also popped up this week from the Transportation Security Administration (TSA), which is in the process of rolling out facial recognition software as an alternative to a human checking your face against your photo ID at the airport.

"The scanning and match is made and immediately overwritten at the Travel Document Checker podium," TSA program analyst Jason Lim told The Washington Post. "We keep neither the live photo nor the photo of the ID." But the agency admitted to the Post for this same report that it does, in fact, keep some photos for up to two years—which means Lim's account is likewise a mere status update (and arguably a dishonest one at that).

We don't keep your data is not We won't keep your data, and it is certainly not We are by law not permitted to keep your data. In the long run, only the last means anything at all.

Beyond its use as a warning, that official duplicity has one other benefit: It can induce a healthy skepticism. It can foster that squeamishness about introducing new technologies and programs that resist their own undoing, both in the grand scheme—after emergency passes or misgivings arrive—and for individuals mistakenly or unfairly affected.

Think, for instance, how difficult it is to get off the terrorist watchlist if you're added in error. Or how hard it will be to argue, if police use of lethal force via robot is normalized, that this arrangement should be undone. Or how the TSA itself has ceased to be an extraordinary measure and now proposes to make a computer, with which there is no reasoning, a primary arbiter of whether you can get on a plane.

Maybe the facial recognition system will be better than dealing with a TSA agent. I doubt it, with the suspicion I apply to all biometric surveillance proposals involving body parts more immutable than fingerprints. But maybe I'm wrong. And, likewise, maybe we'll decide involving more robots in law enforcement is prudent, that it will reduce police mistakes and abuses. Again, I doubt it, given the behavioral incentives robots could introduce, but this is a question on which reasonable people may disagree.

What isn't reasonable, with proliferating questions like these, is assuming all will be well of its own accord, that we have no plans means we won't, that your squeamish impulse is mere Luddism to be suppressed in the face of progress, that the state will voluntarily give up or scale down an indefensible authority once claimed.

Show Comments (45)