Social Security Will Be Insolvent Even Sooner Than Expected, Thanks to COVID-19 Pandemic

A new report from the Social Security Administration expects the program to hit insolvency by 2035. Some experts say it could happen as soon as 2028 if there is a serious recession.

The trustees of the Social Security Administration released their annual report on the program's long-term solvency on Wednesday—but the report is likely already out of date since it doesn't take into account the sharp economic downturn triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Even without the pandemic factoring into the calculations, Social Security is heading for insolvency by 2035, the report says. That doesn't mean the program will be bankrupt, but it represents the date when Social Security's reserves would be used up and mandatory benefit cuts would be instituted across the board. If nothing is done to shore up Social Security, current projections anticipate that beneficiaries will receive only 79 percent of expected benefits, with further cuts needed in future years.

Fifteen years might seem like a long time, but it's really not. Anyone over age 50 today is likely facing the prospect of benefit cuts happening before they retire.

And, again, that doesn't account for the current economic crisis.

If the coronavirus results in economic losses of 15 percent for the current year, the program would likely face insolvency by 2034, says Stephen Goss, chief actuary for the Social Security Administration. Another year of losses would move that date even closer.

"We just don't know if we're going to be back to normal this year, next year, or when," Goss said Thursday during an event hosted by the Bipartisan Policy Center, a centrist think tank.

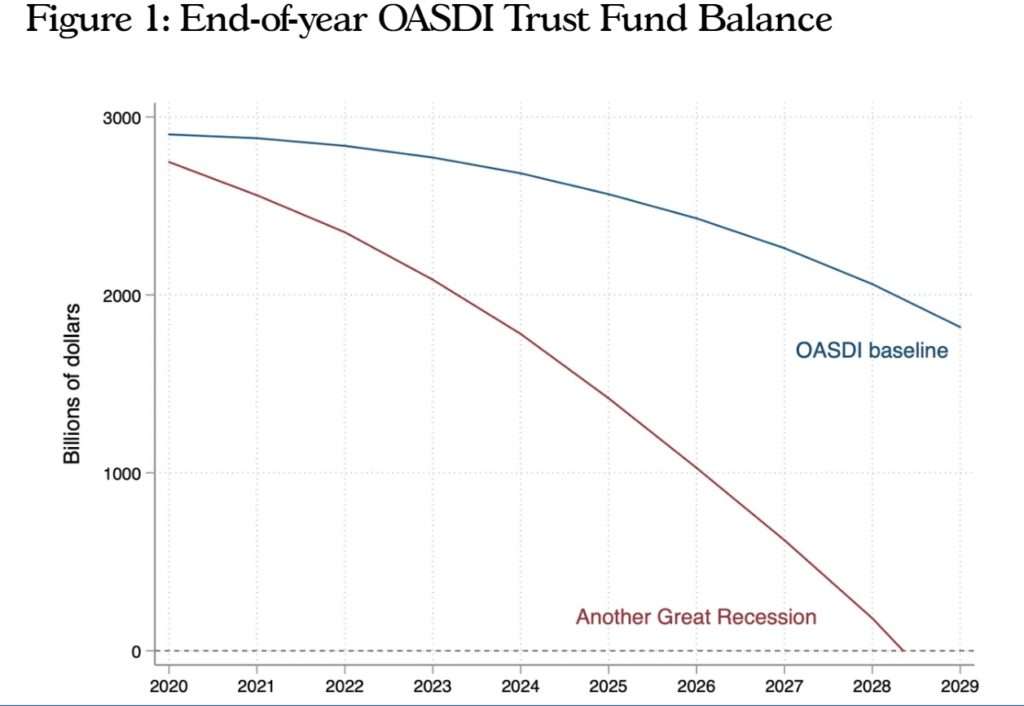

And if the coronavirus response triggers a long-term recession, the urgency of Social Security's status becomes more apparent. According to a projection from the Bipartisan Policy Institute, another recession of the length and depth of the so-called Great Recession that followed the 2008 market crash would cause Social Security to face insolvency before the end of the current decade.

"This is a concerning report, even before the virus crisis hit," says Charles Blahous, senior research strategist for the free market Mercatus Center and a former trustee for Social Security.

More important than the projected dates for insolvency, he says, is the question of how severe the shortfall will be and how long Congress has to act before it arrives. The coronavirus will likely to mean a larger fiscal problem and less time to address it.

As I wrote at this same time last year, the problem facing Social Security is really one of time more than money. If changes can be phased in over a longer period of time, they will be less likely to disrupt retirement plans for current workers or beneficiaries. The last time Congress enacted substantial changes to Social Security was in 1983, and those changes won't be fully adopted until 2027.

It should be obvious that the longer Congress waits to act, the less time will be available for a gradual adjustment.

Any reforms should also consider two systemic problems within the Social Security system. When Social Security launched in 1935, the average life expectancy for Americans was 61. That means the average person died four years before qualifying for benefits. It was imagined as a safety net for the truly needy, not a conveyor belt to transfer wealth from the younger, working population to the older, relatively wealthier retired population.

As a result, the worker-to-beneficiary ratio has shifted dramatically. Last year, there were 64 million Americans getting benefits from Social Security, while 178 million people paid into the system via payroll taxes, according to the trustees' report. That's less than three workers for every beneficiary, a near-historic low.

Congress is going to have to consider all available options, says Blahous. That means changing eligibility ages, moderating benefit growth, and probably hiking payroll taxes too.

"We're not going to have enough from any one of those pots by themselves to be able to close the shortfall," says Blahous, "and that's even before taking into account the worsening that is going to occur as a result of this year's economic slowdown."

Show Comments (92)