Americans Are Losing Their Work Ethic

Even reduced immigration and job openings for miles aren't luring America's ever-growing workforce dropouts back in.

Policy analysts who favor reduced immigration to the United States have always had one plausibly compelling argument: If you cut off the supply of cheaper labor, they maintained, employers would be forced to raise wages for lower-skilled, native-born workers, who would then demonstrate the fiction behind the contention that there were some jobs "Americans just won't do."

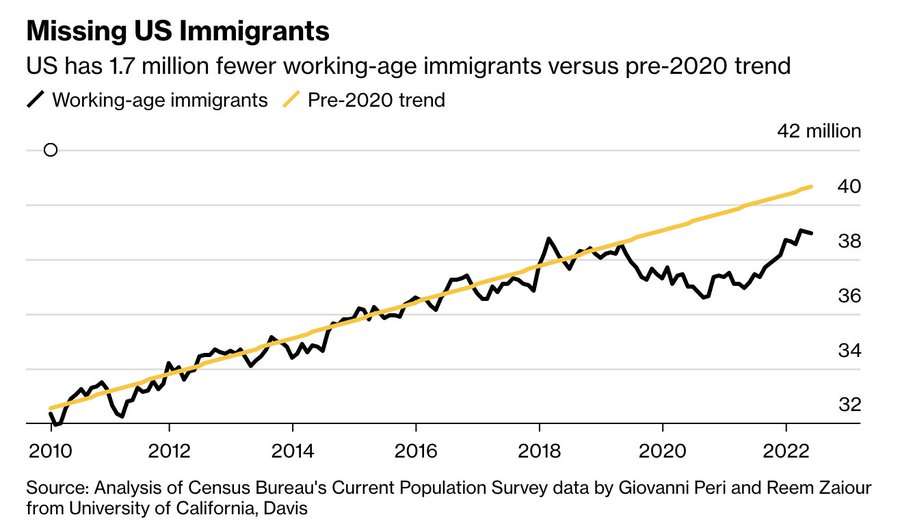

Well, we have just conducted a fascinating real-world test of that hypothesis. Beginning with the restrictionist presidency of Donald Trump in 2017, and then supercharging through the effective 2020–21 border-closure triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. took in about 1.7 million fewer working-age immigrants than would have come at the prior intake rate, according to a recent analysis by Giovanni Peri, economics professor at University of California at Davis.

Meanwhile, absent those immigrants the domestic economy experienced a post-vaccine hiring explosion, with the unemployment rate—which measures the percentage of people actively looking for but failing to find a job—hitting 50-year lows. Inflation-adjusted average wage growth also jumped for a while there, increasing by at least 4 percent annualized for 12 consecutive months.

This should have been the moment when the startlingly high number of prime-aged Americans classified as Not in the Labor Force ("NILFs," no really) got off the sidelines and back into the job market.

And yet: "That did not increase work rates or labor force participation of Americans who are already here," says American Enterprise Institute economist Nicholas Eberstadt, author of the freshly revised (with post-pandemic intro) 2016 book Men Without Work. "We've now got this incredible peacetime labor shortage, and we also have a drop in the number of people in the workforce, by at least a ballpark of 3 million lower than we would have expected on trend before COVID. And that's leaving out immigration, so it's actually lower."

Friday's new jobs report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics underscores America's globally anomalous position: The unemployment rate is at an enviable 3.5 percent, businesses still have 10 million unfilled positions, and yet the labor force participation rate languishes at a miserable 62.3 percent—more than a percentage point lower than before the pandemic.

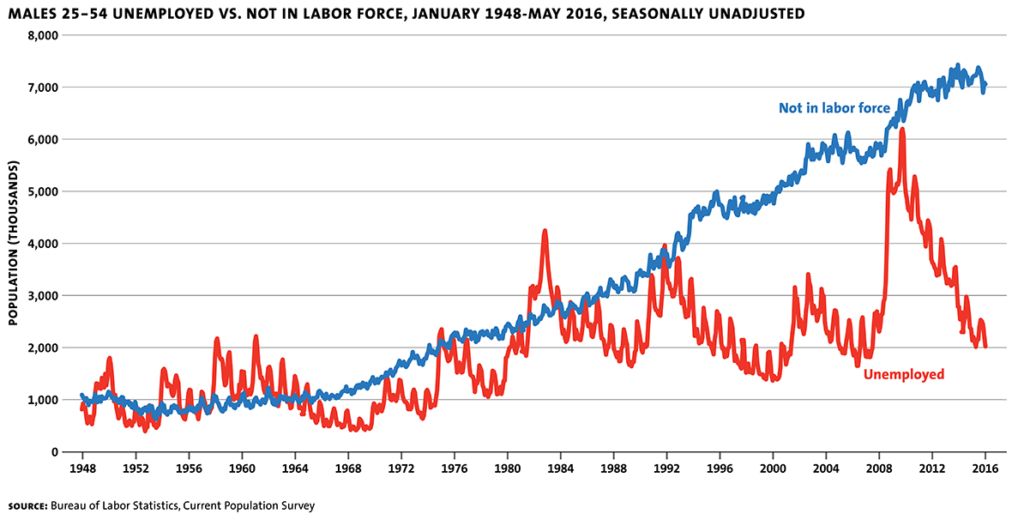

"For every [25–54-year-old] guy who is out of work and looking for a job…in 2022, there are four guys who are neither working nor looking for work," Eberstadt told me this week in an interview for The Fifth Column podcast. "This is the fastest growing component of men in this age group, and it has been the fastest growing component for almost 60 years now."

"Americans," Eberstadt writes in his new introduction, "have been renowned for their work ethic, but the future of that work ethic should not be taken for granted."

The data is startling to behold. A higher percentage of prime-aged American men don't work now—again, at a time of historically low "unemployment"—than during the Great Depression. The United States, where Europeans have always come to work, has a lower labor force participation rate than any European country except Italy (where there are certain, ah, traditions of work activity that escapes traditional measures). And the flight from work has been remarkably steady over time.

"For a trend involving human beings, it's almost a straight line—you can't tell when the recessions came and you can't tell when China entered the WTO," Eberstadt says. "This retreat is so uncannily, weirdly, eerily regular that when I recalculated that line for the latest edition of this book, it basically continued from where the line ended in 2016. It's almost the same straight line, almost identical."

There are no silver-bullet explanations for the American defection from work. Yes, international trade radically changed the face of manufacturing, but that's also true in Canada, which has seen nothing like this dropout rate. Sure, a huge percentage of NILFs—at least half, Eberstadt reckons—are on disability, but it's not like Western Europe is unfamiliar with the welfare state. The United States has, by far, the rich world's highest incarceration rate, which has all kinds of downstream effects on the employability of ex-felons, but even that can only account for a fraction of the shift.

Whatever the cause, the effects of this seismic shift in the labor market have upended everything from civil society to politics.

"There is absolutely nothing good that comes out of this trend," Eberstadt says. "It isn't like the seven million dropouts are working in community gardens or brushing up on their Schopenhauer or whatever. What this trend has meant is slower economic growth for the country, wider income and wealth gaps, more dependence on government welfare programs, more pressure on fragile families, less social mobility, less involvement in society, and a lot more deaths of despair."

It also appears to be habit forming. The employment rate for males between 2001 and 2021 decreased in every age bracket younger than 55, while increasing in every cohort 55 and older, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The younger the group, the more dramatic the drop—16–19-year-old males went from 50 percent to 36 percent. We could be rapidly approaching the moment where half the population hasn't had a job before the age of 25.

Meanwhile, you know who's working the most? Men of Hispanic origin, according to the BLS chart. And immigrants in general.

"It's a very clear picture," Eberstadt says. "No matter what ethnicity you are or what part of the world you come from, if you're an immigrant guy, your workforce participation level rate…is going to be higher than your native-born counterpart. That's true for Latinos, it's true for Asians, true for African-Americans, it's true for Anglos….If you're a foreign-born guy who's married and has no high school degree, your workforce participation profile is essentially indistinguishable from a college-educated, native-born guy."

This historically weird employment picture has potential policy implications aplenty: At minimum, expediting the immigration backlog, rethinking Social Security's disability insurance, and reduce the carceral state.

But we also need some recognition that the status quo cannot last. The shrinking percentage of Americans who do work still work longer and harder than all of their rich-world counterparts, effectively financing the idleness of their contemporaries. Sooner rather than later, that mix will become politically unpalatable.

The experiment of running an economy without immigrants has now been tried, and the native-born dropouts didn't budge. Instead of scapegoating those among us working the hardest, we might consider changing the incentive structures for those who can no longer be moved to work.

Show Comments (370)