U.S. Voters Are 'Vulnerable' to 'Foreign Manipulation,' No Matter How Inept, The New York Times Warns

Journalists who sound the alarm about Russian propaganda are unfazed by the lack of evidence that it has a meaningful impact.

Russia has "reactivate[d] its trolls and bots ahead of Tuesday's midterms," The New York Times warns, aiming to "influence American elections and, perhaps, erode support for Ukraine." According to Times reporter Steven Lee Myers, those online propaganda initiatives "show not only how vulnerable the American political system remains to foreign manipulation but also how purveyors of disinformation have evolved and adapted to efforts by the major social media platforms to remove or play down false or deceptive content."

As with previous panics about Russian "election interference" that was intended to "sow chaos," the details do not match the hype. The example that Myers leads with, a Gab account under the name "Nora Berka," is supposed to illustrate how "vulnerable" voters are to online rants by Russians disguised as Americans and how cleverly those operatives take advantage of U.S. political divisions. But it actually shows how lame these efforts are and how implausible it is to suggest that they have any measurable impact on people's opinions, let alone electoral outcomes.

"After a yearlong silence on the social media platform," Myers breathlessly reports, Berka "resurfaced in August," when she reposted "a handful of messages with sharply conservative political themes before writing a stream of original vitriol." Berka's posts "mostly denigrated President Biden and other prominent Democrats, sometimes obscenely." They "also lamented the use of taxpayer dollars to support Ukraine in its war against invading Russian forces, depicting Ukraine's president as a caricature straight out of Russian propaganda."

How worried should we be that pseudonymous Russians linked to "the Internet Research Agency in St. Petersburg" are adding their voices to the cacophony that passes for online political debate in the United States? Very worried, Myers suggests: "The goal, as before, is to stoke anger among conservative voters and to undermine trust in the American electoral system. This time, it also appears intended to undermine the Biden administration's extensive military assistance to Ukraine."

Yet Myers presents no evidence to suggest that Berka-style commentary has actually advanced those goals. He tells us that Berka's account, which he presents as a prime example of the "Russian trolls and bots" that were "called to action like sleeper cells" in August and September, "has more than 8,000 followers." The account focuses "exclusively on political issues—not in just one state but across the country —and often spreads false or misleading posts." Myers concedes that "most have little engagement," although "a recent post about the F.B.I. received 43 responses and 11 replies, and was reposted 64 times." If that is the most persuasive evidence of Berka's influence that Myers can find, it seems safe to say the republic will survive her faux fulminations.

Myers says "a number of Russian campaigns" have "turned to Gab, Parler, Getter [sic] and other newer platforms that pride themselves on creating unmoderated spaces in the name of free speech." These are "much smaller campaigns than those in the 2016 election, where inauthentic accounts reached millions of voters across the political spectrum on Facebook and other major platforms."

The verb reached is doing a lot of work in that sentence. "Millions" refers to social media users who might have seen posts by "inauthentic accounts." Whether they actually read and digested those messages—and, more to the point, whether the propaganda affected their views or their voting behavior—is a different question. Given the typical quality of these efforts, it seems doubtful that they had a meaningful impact.

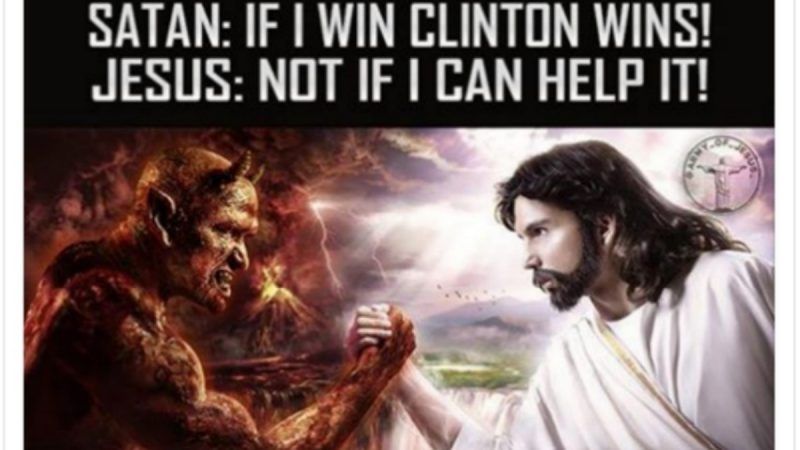

A Facebook ad posted by the "Army of Jesus" in October 2016, for instance, depicted the presidential election as an arm-wrestling match between Satan and the Son of God. "If I win Clinton wins!" Satan said in the headline. "Not if I can help it!" Jesus replied. Politico reported that the ad, which targeted "people age 18 to 65+ interested in Christianity, Jesus, God, Ron Paul and media personalities such as Laura Ingraham, Rush Limbaugh, Bill O'Reilly and Mike Savage, among other topics," generated 71 impressions and 14 clicks.

New York Times reporters and other alarmists warned that the Jesus-and-Satan ad was part of a "disinformation" campaign that aimed to "sow chaos or discord" and "reshape U.S. politics." Facebook said it had identified about 3,000 political ads purchased by 470 or so "inauthentic accounts" that "likely operated out of Russia" between June 2015 and May 2017. The $100,000 spent on those ads was not even a drop in the bucket of Facebook's ad revenue, which totaled $27 billion in 2016. Facebook estimated that "information operations," defined as "actions taken by governments or organized non-state actors to distort domestic or foreign political sentiment," accounted for "less than one-tenth of a percent of the total reach of civic content" during the 2016 presidential campaign.

Myers nevertheless assures us that clandestine Russian propaganda posed a fearsome threat in 2016 because it "reached millions of voters across the political spectrum on Facebook and other major platforms." And while the scale of such efforts is "much smaller" this year, he says, they "are no less pernicious" in "reaching impressionable users who can help accomplish Russian objectives."

To back up that counterintuitive claim, Myers quotes Brian Liston, "a senior intelligence analyst with Recorded Future who identified the Nora Berka account." Although the audiences on alternative social media platforms such as Gab, Parler, and Gettr are "much, much smaller than on your other traditional social media networks," Liston avers, "you can engage the audiences in much more targeted influence ops because those who are on these platforms are generally U.S. conservatives who are maybe more accepting of conspiratorial claims."

The 2016 messages tied to Russia were also "targeted," as the placement of the Jesus-and-Satan ad illustrates. And the fact that many conservatives endorse wacky conspiracy theories does not mean they need foreign aid to do so.

In case Berka's mockery of Biden is not enough to show "how vulnerable the American political system remains to foreign manipulation," Myers also notes "a recent series of cartoons that appeared on Gab, Gettr, Parler and the discussion forum patriots.win." The cartoons, identified as the work of "an artist named 'Schmitz,'" "disparaged Democrats in the tightest Senate and governor races."

One cartoon "targeting Senator Raphael Warnock of Georgia, who is Black, employed racist motifs," while "another falsely claimed that Representative Tim Ryan, the Democratic Senate candidate in Ohio, would release 'all Fentanyl distributors and drug traffickers' from prison." Myers concedes that "the cartoons received little engagement and did not spread virally to other platforms." He nevertheless wants us to believe that such awful stuff poses a qualitatively different threat to "the American political system" than equally awful stuff produced by actual U.S. citizens.

Myers admits "it may be hard to measure the exact impact of these accounts on voters come Tuesday." But "at a minimum," he says, they "contribute to what Edward P. Perez, a board member with the OSET Institute, a nonpartisan election security organization, called 'manufactured chaos' in the country's body politic."

At the same time, Myers suggests that Americans don't really need Russian assistance to engage in ill-informed, dishonest, or hyperbolic political discussions. "While Russians in the past sought to build large followings for their inauthentic accounts on the major platforms," he says, paraphrasing Perez, "today's campaigns could be smaller and yet still achieve a desired effect—in part because the divisions in American society are already such fertile soil for disinformation." Since 2016, Perez says, "it appears that foreign states can afford to take some of the foot off the gas," because "they have already created such sufficient division that there are many domestic actors to carry the water of disinformation for them."

Although the premise that "foreign states" are responsible for "division" among Americans is highly dubious, researchers like Perez and journalistic accomplices like Myers take it for granted. No matter how puny, unsophisticated, or seemingly ineffectual Russian "disinformation" might be, it is always a grave threat to democracy because Americans are so "impressionable," especially when their political views lean right. Those rubes accept implausible claims without asking for evidence, as long as the claims reinforce their preexisting beliefs. The Times seems blithely unaware that it is illustrating the same tendency.

Show Comments (207)