Absolute Immunity Puts Prosecutors Above the Law

By giving powerful law enforcement officials absolute immunity from civil liability, the Supreme Court leaves their victims with no recourse.

When a storm flooded Baton Rouge in 2016, Priscilla Lefebure took shelter with her cousin and her cousin's husband, Barrett Boeker, an assistant warden at the Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola. During her stay at her cousin's house on the prison grounds, Lefebure later reported, Boeker raped her twice—first in front of a mirror so she would have to watch, and again days later with a foreign object.

Lefebure's allegations led to a yearslong court battle—not against her accused rapist but against District Attorney Samuel C. D'Aquilla, who seemed determined to make sure that Boeker was never indicted. As the chief prosecutor for West Feliciana Parish, which includes Angola, D'Aquilla sabotaged the case before it began.

When a grand jury considered Lefebure's charges, D'Aquilla declined to present the results of a medical exam that found bruises, redness, and irritation on Lefebure's legs, arms, and cervix. Instead, he offered a police report with his own handwritten notes, which aimed to highlight discrepancies in her story. D'Aquilla opted not to call as witnesses the two investigators on the case, the nurse who took Lefebure's rape kit, or the coroner who stored it. And he refused to meet or speak with Lefebure at all, telling local news outlets he was "uncomfortable" doing so.

The lawyer that Boeker hired to represent him was a cousin of the district attorney, Cy Jerome D'Aquila (who spells his name slightly differently). Boeker did not need his services very long, since the grand jury predictably declined to indict him.

After that fiasco, Lefebure sued Samuel D'Aquilla in federal court, saying Boeker falsely claimed his encounters with her were consensual and sought D'Aquilla's assistance in blocking rape charges. According to the lawsuit, D'Aquilla was happy to help. Lefebure accused D'Aquilla of violating her rights to equal protection and due process by deliberately crippling her case against Boeker.

Such lawsuits typically are doomed from the start, because prosecutors enjoy absolute immunity for actions they take in the course of their prosecutorial duties. That means victims of prosecutorial malfeasance cannot seek damages even for blatant constitutional violations. When district attorneys falsify evidence, knowingly introduce perjured testimony, coerce witnesses, or hide exculpatory information from the defense, their victims generally have no legal recourse. And although such misconduct theoretically can trigger professional disciplinary action, including disbarment, that rarely happens.

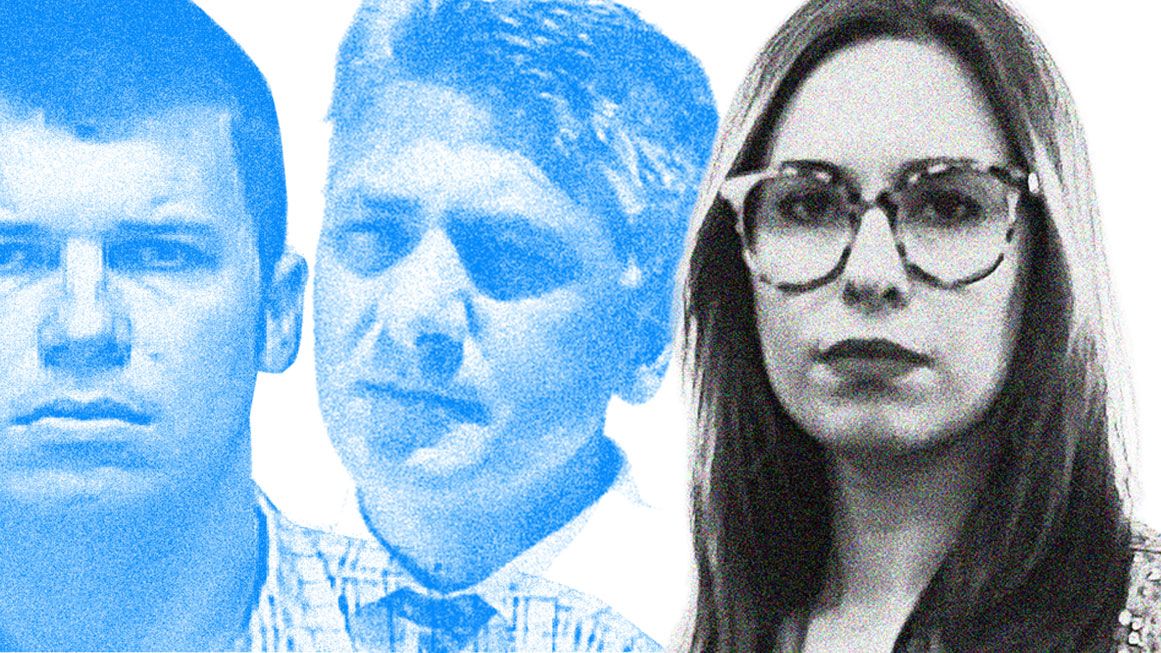

While debates about criminal justice reform tend to fracture along political lines, prosecutorial immunity need not be a partisan issue. One of Lefebure's attorneys, Jack Rutherford, is a prominent transgender lawyer with progressive political commitments. Her other attorney, prior to his death in September, was Ken Starr, the Republican whose investigation led to former President Bill Clinton's impeachment. When the government appealed a federal judge's decision in Lefebure's favor, the American Conservative Union, the group that puts on the annual Conservative Political Action Conference, filed a brief on her behalf, as did several victim advocacy groups.

The members of this unlikely coalition may not see eye to eye on much, but they agree that government officials should not have carte blanche to abuse their powers.

'The Wrongs Done by Dishonest Officers'

The Supreme Court announced the doctrine of absolute immunity for prosecutors in the 1976 case Imbler v. Pachtman. The Court ruled that a man who had spent years in prison could not sue a prosecutor who allegedly withheld evidence that ultimately exonerated him. The justices approvingly quoted a sentiment that Learned Hand expressed as a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit in 1949: "It has been thought better to leave unredressed the wrongs done by dishonest officers than to subject those who try to do their duty to the constant dread of retaliation."

Absolute immunity for prosecutors was a product of judicial activism at the highest level, and it seemed to contradict the plain meaning of federal law. Under Title 42, Section 1983 of the U.S. Code, a provision of the Civil Rights Act of 1871, "every person" who deprives someone of constitutional rights "under color of any statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage, of any State" is "liable to the party injured," who can seek damages in federal court.

Despite that broad language, the Supreme Court has grafted exceptions onto the statute. They include "qualified immunity," which shields police and other government officials from Section 1983 liability unless their alleged misconduct violated "clearly established" law. Meeting that requirement can be close to impossible, since courts often demand that plaintiffs cite precedents with nearly identical facts. Absolute immunity goes further, blocking lawsuits against prosecutors even when it is beyond dispute that their actions were unconstitutional.

Although Imbler was the first time the Supreme Court had addressed the issue, the majority said federal appeals courts were "virtually unanimous that a prosecutor enjoys absolute immunity from [Section 1983] suits for damages when he acts within the scope of his prosecutorial duties." The justices located the basis for that conclusion in the immunity that judges had long received under the common law for judicial acts.

The Court noted that appeals courts "sometimes have described the prosecutor's immunity as a form of 'quasi-judicial' immunity." It said "the functional comparability of their judgments to those of the judge…has resulted in both grand jurors and prosecutors being referred to as 'quasi-judicial' officers, and their immunities being termed 'quasi-judicial' as well."

When the Civil Rights Act of 1871 was passed, attorney Scott A. Keller explains in a 2021 Stanford Law Review article, the common law gave judges "immunity for their discretionary duties without asking whether they acted in bad faith." In addition to officials who oversaw trials, absolute immunity extended to jurors and "high-ranking executive officers—those exercising core, fully discretionary executive powers." But courts "had not yet begun to grant government prosecutors absolute immunity." Instead, "prosecutors and all other lower-ranking executive officers performing discretionary duties had a freestanding qualified immunity, which could be overcome if a plaintiff established clear evidence of subjective malice."

In the 1967 case Pierson v. Ray, the Supreme Court held that Section 1983 had not abolished absolute immunity for judges. In Imbler it went further, ruling that prosecutors enjoyed the same sort of immunity, contrary to what courts had held in the 19th century. As with judges, there is no exception for bad-faith decisions like those Lefebure accused D'Aquilla of making.

Thanks to that doctrine, courts have blocked Section 1983 lawsuits even in cases alleging egregious misconduct. In the 1994 case Dory v. Ryan, for example, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit approved absolute immunity for a prosecutor who allegedly coerced a witness to lie in testimony against a man who was then convicted and imprisoned for a drug crime. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit reached a similar conclusion in the 2003 case Cousin v. Small, which involved a man who spent a year on death row after the prosecutor allegedly withheld exculpatory evidence from the defense.

A year later in Bernard v. County of Suffolk, the 2nd Circuit said prosecutors could not be sued for putting government officials on trial to satisfy a political vendetta. "Racially invidious or partisan prosecutions, pursued without probable cause, are reprehensible," the court said, "but such motives do not necessarily remove conduct from the protection of absolute immunity."

Even when prosecutors behave reprehensibly, federal judges worry that allowing a civil remedy would invite a flood of frivolous lawsuits that would drown the criminal justice system. Clark Neily, a former constitutional litigator who now is senior vice president for legal studies at the libertarian Cato Institute, says "there's no empirical basis" for that fear.

Without absolute immunity, there would still be strong deterrents against filing groundless claims. In addition to paying court fees, a plaintiff has to find a lawyer who is willing to take on the case and go up against taxpayer-financed litigators. Lawyers typically do that in exchange for a contingency fee, meaning they will get paid only if they win at trial or secure a settlement. Attorneys therefore have a strong financial incentive to avoid frivolous claims.

Lawyers also understand that most judges are former prosecutors and that attorneys can jeopardize their careers if they earn reputations for targeting prosecutors without a solid basis. "I don't know any lawyers that would take that lightly and bring a [frivolous] case against a prosecutor—probably the most powerful government official in America," Neily says. "The magnitude of that risk is almost inexpressible."

The Prosecutor Who Was Also a Judge

When that power is abused, it can wreak havoc on the justice system, as Ralph Petty demonstrated for two decades. By day, Petty was an assistant district attorney in Midland, Texas, arguing cases against the accused. By night, he clerked for the same judges in the same courthouse, which gave him access to confidential information that the defense did not see. He spent evenings writing rulings in favor of the government, otherwise known as himself. And he earned more than $250,000 in the process.

Petty managed this covert balancing act for nearly 20 years. Midland County District Attorney Laura A. Nodolf caught wind of it when she came across his accounting records in 2019, the same year he retired, and an exposé by USA Today publicly revealed Petty's illegal side hustle in February 2021. His misconduct stripped defendants of their due process rights in more than 300 cases, including one that nearly killed a man.

In 2003, Clinton Young arrived on death row after he was convicted of murder. As one of the prosecutors on that case, Petty simultaneously worked for the presiding judge, John Hyde, despite the fact that prosecutors are prohibited from discussing ongoing cases with judges in private. But Petty did not just talk with Hyde; he was Hyde's right-hand man.

It was a relationship that proved fruitful for Petty. In an April 2021 decision recommending that Young receive a new trial, Senior District Judge Sid Harle found it was more likely than not that Petty's private communications with Hyde, who died in 2012, "at the very least…contributed to" a series of judicial rulings that favored the government over Young.

Worse, it seems that several orders Hyde issued were drafted by Petty himself. Harle noted that the orders had a "distinctive style and format" that was characteristic of Petty and that "differ[ed] from other documents prepared by the Court and other members of the Midland DA." Those orders addressed the instructions to Young's jury, the jury verdict forms, the judgment of capital murder and sentence of death, and Young's request for a new trial, which Hyde rejected.

Young, who has maintained his innocence for decades, was removed from death row in January 2022 pending a new trial. Harle ruled that Petty's "shocking" actions "destroyed any semblance of a fair trial."

The cost to Young is hard to calculate. "I missed my 20s," he says. "I missed most of my 30s. By now, I'd have my own home….I'd have a family, I'd have kids by now. I don't know how to put it."

Petty's malfeasance may have deprived hundreds of people of their liberty, and he came close to sending a possibly innocent man to his death. Yet it will be nearly impossible for his victims even to ask for financial recompense.

In 2001, Petty successfully prosecuted Erma Wilson for drug possession—a charge she vehemently denies to this day. She rejected multiple plea deals, intent on proving her innocence in court. But that is difficult to do when your prosecutor is also your de facto judge.

More than two decades later, Wilson, who is suing Petty, is still dealing with the consequences of that conviction. She could not fulfill her childhood dream of becoming a nurse, which was precluded by Texas licensing laws that disqualify people convicted of drug felonies. "All I want now is to hold Petty and Midland County's entire judicial system accountable, so other prosecutors will think twice before violating the people's rights," she said after Petty's misconduct came to light. "There is nothing that can be done to give me back the past 20 years of my life or my missed nursing career, but I can ensure that similar violations don't happen to others."

It's a mission that former federal public defender* Lara Bazelon, a law professor at the University of San Francisco, also has undertaken. A crucial part of the Supreme Court's justification for absolute immunity is the assumption that rogue prosecutors will face professional discipline. Putting that assumption to the test, Bazelon has spent the last several years filing complaints with the State Bar of California against prosecutors who leave a trail of professional abuse. She pores over the evidence and compiles the exhibits. "I do [the bar's] work for them," she says.

One of Bazelon's complaints involved former San Francisco Assistant District Attorney Linda Allen. According to a 2014 decision by a California appeals court, Allen committed "highly prejudicial misconduct" when she secured Jamal Trulove's 2010 murder conviction by lying about the only supposed eyewitness to the crime.

The appeals court overturned Trulove's conviction, and he was acquitted at his second trial in 2015. "If that state bar is ever going to discipline a prosecutor," Bazelon told me in January 2022, "it's going to be this one."

It was not. Despite Allen's deceit, Bazelon's complaint died on arrival. "The state bar is entirely unwilling to do its job even when its job is done for them," she says. "Their reasoning wouldn't fly in my sixth-grade daughter's classroom."

Bazelon has filed nine such complaints, none of them successful. "It is outrageous and undermines the Supreme Court's promise that absolute immunity for prosecutors is just fine because they will be disciplined by the bar," she says. "They won't be. And until they are, we will have more Jamal Truloves."

With Great Power Comes No Responsibility

The National Police Accountability Project notes that "absolute immunity for prosecutors is especially dangerous as the current system already incentivizes prosecutors to secure convictions at all costs, with promotions, reelection, and elevation to higher office often contingent on procuring as many convictions as possible." Prosecutors know they are shielded almost entirely from accountability for job-related misconduct. Why follow the Constitution when it is effectively optional?

That question was thrust into the mainstream during the widespread protests against police abuse in the summer of 2020. Qualified immunity, once a niche topic discussed almost exclusively among policy wonks, became a topic of dinner-table conversation overnight. But absolute immunity slid under the radar. "Qualified immunity makes it very, very difficult to sue government officials," observes Institute for Justice senior attorney Patrick Jaicomo, while absolute immunity "makes it impossible."

Police officers, who are protected by qualified immunity, continue to receive widespread scrutiny. Prosecutors have largely evaded it, notwithstanding the fact that they exercise greater power with less accountability. Yet while absolute immunity remains a relatively obscure issue, a cross-ideological consensus against it seems to be developing, as reflected in Lefebure's case.

"This case is ultimately about the rule of law and the constitution of democracy," Starr told Reason in an April interview shortly before his death. It is hard to support limited government, personal responsibility, and law and order while arguing that powerful officials should be able to violate people's rights with impunity.

Surprisingly, Lefebure's lawsuit made some headway. In 2019, a federal judge in Louisiana ruled that Lefebure could proceed with some of her claims, emphasizing a distinction that the Supreme Court has drawn between prosecutorial and investigative functions. U.S. District Judge Shelly D. Dick concluded that D'Aquilla's "alleged conduct in failing to request, obtain, and examine the rape kit; making notes on the police report; and failing to interview the Plaintiff prior to the grand jury hearing were investigative functions for which absolute immunity does not apply."

Two years later, a divided panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit overturned Dick's ruling. "If anyone deserves to have her day in court, it is Priscilla Lefebure," Judge James C. Ho wrote for the majority. "The allegations in her complaint are sickening."

Ho said that "Lefebure's story is particularly appalling because her alleged perpetrator holds a position of significance in our criminal justice system as an assistant prison warden." He added that "Lefebure deserved to have the support of her state's elected and appointed prosecutors, investigators, and other officials in her pursuit of justice." If "her account is correct," he wrote, "the system failed her—badly."

Unfortunately, Ho said, "Supreme Court precedent makes clear that a citizen does not have standing to challenge the policies of the prosecuting authority unless she herself is prosecuted or threatened with prosecution….We are horrified by the allegations in this case—the repeated acts of rape and sexual assault, followed by grotesque acts of prosecutorial misconduct. But we have no authority to overturn Supreme Court precedent."

That ruling elicited a rare rebuke from three retired federal judges: former 9th Circuit Judge Alex Kozinski, former U.S. District Judge F.A. Little Jr., and former U.S. District Judge Michael Mukasey, who also served as President George W. Bush's final attorney general. "It shocks any semblance of a decent sensibility that there are places left in America where a sheriff and district attorney routinely fail to collect and process rape kits, where an assailant's 'we got a little rough' is accepted at face value by law enforcement, where the victim is the one investigated, and where the well-connected can avoid spending even a night in jail after being arrested on suspicion of the most depraved conduct," the trio wrote, adding that the ruling did away with "an entire class of law enforcement-related equal protection claims."

The 5th Circuit's decision left Lefebure with one last option. Her lawyers pleaded with the Supreme Court to take up the case and send a message that government officials like D'Aquilla are not above the law they are supposed to uphold. In May, as the Court's term was nearing its end, the justices declined to consider Lefebure's appeal.

Justice vs. Precedent

Lefebure v. D'Aquilla is not the only case in which Ho has bemoaned the gap between justice and Supreme Court precedent. "Worthy civil rights claims are often never brought to trial," he observed in May. "That's because an unholy trinity of legal doctrines—qualified immunity, absolute prosecutorial immunity, and Monell v. Department of Social Services of City of New York [a 1978 case involving municipal liability for official misconduct]—frequently conspires to turn winnable claims into losing ones."

Ho was responding to a lawsuit by Michael Wearry, a Lousiana man whose capital murder conviction was overturned by the Supreme Court in 2016. Wearry sued District Attorney Scott M. Perrilloux and Livingston Parish Sheriff's Detective Marlon Foster, accusing them of fabricating evidence against him. The majority of a 5th Circuit panel ruled that neither defendant was protected by absolute immunity, since the allegations involved investigation rather than prosecution.

Ho wrote a separate opinion in which he acknowledged that "the doctrine of prosecutorial immunity appears to be mistaken as an original matter" but concluded that the lawsuit was foreclosed by that doctrine. "The majority says it is 'strange' to apply prosecutorial immunity here," he wrote. "I agree. But a faithful reading of precedent requires us to grant it here, no matter how troubling I might personally find it."

Federal courts often concede that officials have violated the Constitution while in the next breath shielding them from facing a jury, saying that is what judicially constructed immunity doctrines demand. "Congress decides what our laws shall be," Ho noted in Wearry v. Foster. "Congress can abolish qualified immunity, absolute prosecutorial immunity, and Monell. And it can do so anytime it wants to."

Until that happens, it is unlikely much will change. If Lefebure's case is any indication, the Court is not inclined to revisit these precedents, even though it created this problem to begin with.

For now, accountability for the most powerful government actors will continue to be the exception. Ralph Petty, the moonlighting court clerk, was disbarred in 2021, two years after he retired in style. Linda Allen, the prosecutor in San Francisco, lost her job there in 2020 but was promptly hired by neighboring Santa Clara County. Samuel D'Aquilla still works in the same judicial district.

Boeker, the assistant prison warden at Angola, kept his job for nearly four years years after Lefebure accused him of raping her. He ultimately got the boot in May 2020, shortly before he was arrested on felony charges—not for the alleged rapes, but for assaulting an inmate with a fire extinguisher.

*CORRECTION: The original version of this article misstated Bazelon's former profession.

Show Comments (149)