5 Profiles in Courage and Cowardice in a Trump-Dominated GOP

Here is how Mitch McConnell, Mike Pence, Liz Cheney, Ted Cruz, and Josh Hawley responded to the president's election delusions.

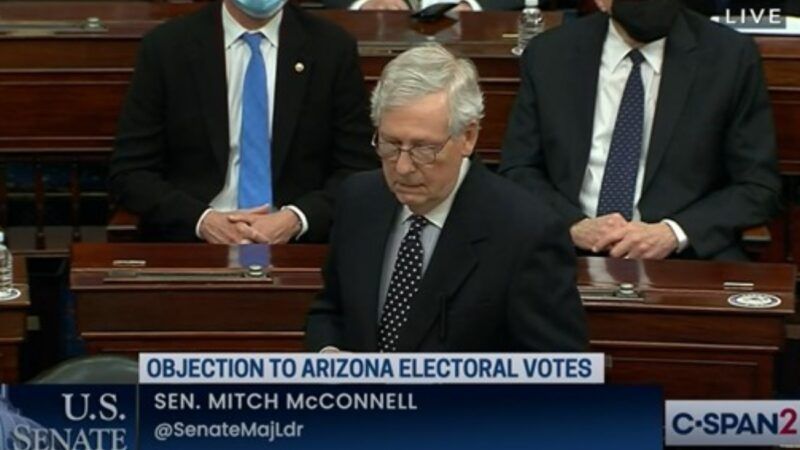

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R–Ky.), who steadfastly resisted Donald Trump's first impeachment and did not acknowledge President-elect Joe Biden's victory until more than a month after the election, is reportedly pleased by today's vote to impeach Trump a second time. McConnell "has concluded that President Trump committed impeachable offenses and believes that Democrats' move to impeach him will make it easier to purge Mr. Trump from the party," The New York Times reports, citing "people familiar with Mr. McConnell's thinking."

McConnell's striking turnaround after four years of unquestioning loyalty to Trump is a hopeful sign that the Republican Party may eventually stand for something other than the whims of an authoritarian demagogue. But the fact that McConnell's "thinking" about the merits of tying the GOP's future to Trump did not change decisively until his own workplace was attacked by the president's deluded followers suggests it would be foolhardy to bet that his party can salvage any principles that are worth defending.

Even before last week's deadly invasion of the Capitol, McConnell, to his credit, forcefully rejected efforts to challenge duly certified electoral votes for Biden. "If this election were overturned by mere allegations from the losing side, our democracy would enter a death spiral," he warned less than an hour before he was forced to flee the president's enraged fans. "We would never see the whole nation accept an election again," he added, and "every four years would be a scramble for power at all cost."

Based on "sweeping conspiracy theories," McConnell noted, "President Trump claims the election was stolen," but "nothing before us proves illegality anywhere near the massive scale…that would have tipped the entire election." He added that "public doubt alone" cannot "justify a radical break" from historical practice "when the doubt itself was incited without evidence."

These were strong words, but they came two months too late. From the moment that Trump began insisting that he actually won the election by a landslide, it was clear that the president's conviction had no basis in reality. Yet McConnell humored Trump, neither backing nor rejecting his wild claims, based on the premise that Biden's victory should not be conceded until the president had exhausted his legal options and the Electoral College had met. In the meantime, the fantasy underlying last week's riot grew and spread, unchallenged by all but a few Republican legislators.

One of those honorable exceptions was Rep. Liz Cheney (R–Wyo.), the third-ranking Republican in the House. Cheney, like McConnell, initially said "it's the responsibility of the courts" to address election fraud claims. But by November 20—the day after the president's legal team held a bizarre press conference highlighting the loony conspiracy theory promoted by Trump, Rudy Giuliani, and Sidney Powell—she was losing patience.

"The President and his lawyers have made claims of criminality and widespread fraud, which they allege could impact election results," Cheney said. "If they have genuine evidence of this, they are obligated to present it immediately in court and to the American people."

In an interview with NBC News after the Capitol riot, Cheney did not mince words about the threat it represented or about Trump's role in it:

We have very deep and clear political differences in this country, but we don't resolve those differences by mob violence. It doesn't matter what side of those issues you stand on. The president of the United States' statement [after the riot started], in my view, was completely inadequate. What he has done and what he caused here is something that we've never seen before in our history. It has been 245 years, and no president has ever failed to concede or agree to leave office after the Electoral College has voted. I think what we're seeing today is a result of that—a result of convincing people that somehow Congress was going to overturn the results of this election, a result of suggesting he wouldn't leave office. Those are very, very dangerous things. This will be remembered and this will be part of his legacy, and it is a dangerous moment for our country.

Cheney was one of several Republicans in the House who supported Trump's impeachment today. "The President of the United States summoned this mob, assembled the mob, and lit the flame of this attack," she said in a press release on Tuesday. "Everything that followed was his doing. None of this would have happened without the President. The President could have immediately and forcefully intervened to stop the violence. He did not. There has never been a greater betrayal by a President of the United States of his office and his oath to the Constitution."

Vice President Mike Pence's role in all of this was closer to McConnell's than Cheney's. Like McConnell, he did not challenge Trump's fantasy until it was too late. And like McConnell, he eventually sided with the Constitution rather than the president.

"I do not believe that the Founders of our country intended to invest the Vice President with unilateral authority to decide which electoral votes should be counted during the Joint Session of Congress, and no vice president in American history has ever asserted such authority," Pence said in a statement he issued shortly before he presided over the joint session of Congress convened to affirm Biden's victory. "It is my considered judgment that my oath to support and defend the Constitution constrains me from claiming unilateral authority to determine which electoral votes should be counted and which should not." But that came after weeks of dithering as Trump repeatedly pressured Pence, in public and in private, to exercise a power he does not have.

"Pence had a choice between his constitutional duty and his political future, and he did the right thing," University of California, Berkeley, law professor John Yoo told The New York Times. "I think he was the man of the hour in many ways—for both Democrats and Republicans. He did his duty even though he must have known, when he did it, that that probably meant he could never become president."

Yoo is a vigorous and controversial champion of executive authority who opposed Trump's first impeachment but has criticized the president for asserting nonexistent powers. He was one of the legal scholars Pence consulted as he decided whether to do Trump's unconstitutional bidding, which should not have been a hard call.

Rep. Tom Malinowski (D–N.J.) was less impressed than Yoo by Pence's courage. "I'm glad he didn't break the law, but it's kind of hard to call somebody courageous for choosing not to help overthrow our democratic system of government," Malinowski told the Times. "He's got to understand that the man he's been working for and defending loyally is almost single-handedly responsible for creating a movement in this country that wants to hang Mike Pence."

Former Sen. Jeff Flake (R–Ariz.), a longtime Trump critic, split the difference. "There were many points where I wished he would have separated, spoke out, but I'm glad he did it when he did," Flake said. "I wish he would have done it earlier, but I'm sure grateful he did it now."

Even McConnell and Pence are models of bravery compared to Sens. Ted Cruz (R–Texas) and Josh Hawley (R–Mo.), who led the legally groundless objections to Biden's electoral votes in the Senate. In doing so, they cynically and recklessly reinforced the twin delusions that gave rise to last week's violence: that Trump won the election and that Biden's inauguration could still be prevented.

At the same time, neither Cruz nor Hawley had the guts to explicitly endorse those beliefs. They calculated that they could reap the political benefits of kowtowing to the president's supporters without paying the political cost of looking like kooks. It apparently never entered the minds of these two Ivy League lawyers that they might pay a cost for so blatantly trying to advance their careers by sacrificing their supposed devotion to the Constitution. The crucial question for the Republican Party now is whether they were right to ignore that possibility.

[This post has been updated with additional comments by Cheney.]

Show Comments (146)