In Alaska, Ranked Choice Voting Worked

Partisan outrage over Sarah Palin's defeat shouldn't obscure the obvious benefits of better voting systems.

For the second time in four months, Sarah Palin's attempted political comeback was foiled by voters in Alaska, who reelected Rep. Mary Peltola (D–Alaska) to the state's lone seat in the House of Representatives.

And, yes, it was the voters who picked Peltola, not the system.

Just as happened when Peltola defeated Palin in a special election during the summer, some conservatives have been quick to blame the former governor's defeat on Alaska's recently adopted open-primary/ranked choice voting system. "Ranked choice voting has once again resulted in an election outcome totally unrepresentative of Alaska sentiments, just as supporters wanted," tweeted conservative columnist Ben Domenech shortly after the results of Palin's race were announced on Wednesday night. Domenech was echoing similar complaints lodged by high-profile Republicans, like Sen. Tom Cotton (R–Ark.), who called ranked choice voting "a scam" after Palin lost to Peltola in August's special election for the same House seat.

Those complaints are mostly just partisan hackishness, the sort of excuse making that people on all sides engage in after disappointing elections. Because nonpartisan primaries and ranked choice voting are not commonly used, however, it's worth exploring and debunking these claims.

Far from being a scam or an unrepresentative voting method, ranked choice voting actually encourages voters to look beyond partisan markers and choose (or block) candidates based on their merits.

Under Alaska's new election system, all candidates compete in a single primary contest—rather than in party-specific contests—with the top four vote-getters advancing to the general election. That meant that the general election ballot for Alaska's congressional seat contained four names on Election Day, with Republican Nick Begich and Libertarian Chris Bye qualifying alongside Palin and Peltola.

In the general election, ranked choice voting is used to determine the winner. That means that every voter ranks their choices from one through four. As the votes are counted, there is an "instant runoff" in which votes cast for losing candidates are reallocated to reflect the ranks assigned by individual voters.

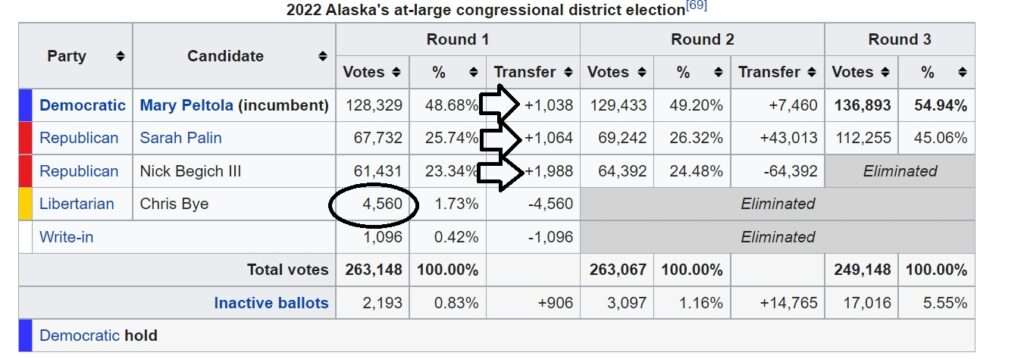

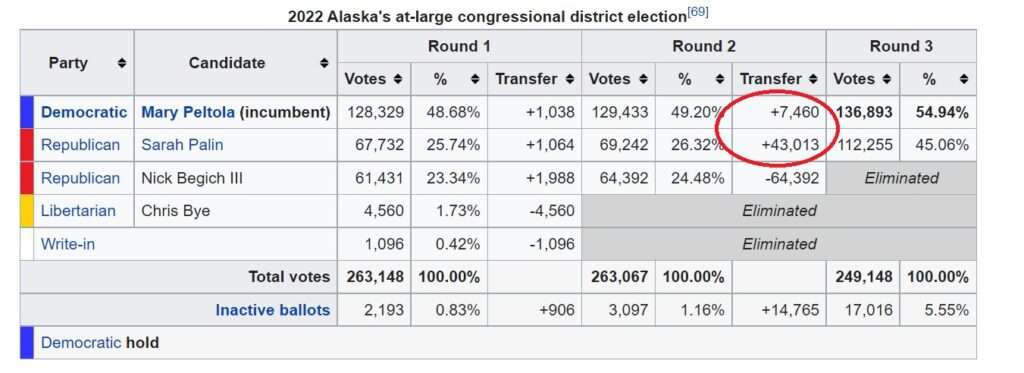

To see how this works in practice, let's look at Chris Bye, who finished last in the first round of vote counting. He received 4,560 first-place votes. After being eliminated, those ballots were re-distributed to the other candidates. Begich was the second choice of 1,988 Bye voters, so he received those ballots for the second round. Palin was the second choice of 1,064 Bye voters, and Peltola was the second choice for 1,038 of them.

At that point, no candidate had more than 50 percent of the total, so an additional elimination was necessary. Despite getting a plurality of Bye's votes, Begich was still in third place, so he was eliminated and his votes were reallocated to Palin and Peltola. Voters who had picked Begich as their first choice had their ballots distributed to their second-place choice (unless the second-place choice was Bye), while Bye voters who'd picked Begich second had their votes redistributed to whomever they'd picked as their third choice.

As you might expect since both were Republicans, a majority of Begich's ballots ended up in Palin's pile. But not all of them, and the Begich-to-Peltola pipeline was enough to push the Democratic incumbent over the 50 percent threshold.

Now, here's where the partisan hacks get their boxers in a bind. They look at the first-round totals, see that most Alaskans picked a Republican as their top choice, and conclude that a Republican must therefore represent the state in Congress.

And, of course, that might have been the result if the election was held with single-party primaries and then a single Republican vs. a single Democrat in the general election, as happens in most places in America. But just because that system is more widely used doesn't mean it is more representative, more fair, or more legitimate. Indeed, the chief problem with the more traditional election system is that it forces voters to hold their noses and pick between two bad options. Parties love that, because it means less competition, but the result is a lot of zero-sum politicking and bad policies. And it gives outsized political power to primary election voters, allowing fringe candidates to win power without being broadly endorsed by the general electorate.

Which brings us back to Palin. As in August, she lost because not enough Alaskan voters picked her to represent them in Congress. It's really as simple as that. Ranked choice voting rewards candidates who are viewed as being acceptable even if not ideal by the majority of voters. Palin, for the second time in a handful of months, failed that test.

There are no broader conclusions to be drawn here. Alaska's system doesn't disadvantage Republicans. In fact, in other races, it helped them!

In the state House, Republicans had the lead in just 19 of the 40 districts after the first round of votes were counted earlier this month. After the "instant runoffs" were completed, however, GOP candidates had come from behind to win two additional districts—enough to give Republicans a slim majority in the chamber.

Republicans can also thank ranked choice voting for helping the party hold a crucial seat in the U.S. Senate. In a traditional party-primary system, Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R–Alaska) likely would have been ousted by her Trump-backed challenger, Kelly Tshibaka. Given how other Trump-backed Senate candidates performed in the general election, it's worth wondering whether Tshibaka would have been able to hold the state. Instead, Murkowski narrowly won reelection, in part because she was the preferred second choice of voters who'd initially backed Democratic candidate Pat Chesbro.

Once again, the system rewarded a candidate who was seen as an acceptable alternative. Or, if you like, it punished a candidate who was seen as unacceptable—although Murkowski had narrowly defeated Tshibaka in the first round of voting as well.

This is exactly what the combination of open primaries and ranked choice voting is supposed to do. It encourages voters to express nuanced opinions about individual candidates rather than asking them to blindly mash the "R" or "D" button after being fueled up with months of campaign rage porn. It turns elections into less of a political Super Bowl and more of an actual attempt to gauge the desires of the voting public and triangulate representation around those interests.

"There's every reason to think the wins for Sen. Lisa Murkowski and Rep. Mary Peltola reflect Alaska voters' well-considered preferences," tweeted Walter Olson, a senior fellow for constitutional studies at the libertarian Cato Institute. "Ranked choice voting and the universal primary with which it's paired in Alaska performed as one would want them to. More, please."

No election system is going to be perfect all the time, of course. Each will have its own weird wrinkles and produce the occasional unusual result—and ongoing tweaks to produce even more representative outcomes should be considered

But the one thing that absolutely should not happen is judging the merits of different systems based on which party wins. And if Republicans are unhappy about this outcome, then maybe they should run better candidates next time.

Show Comments (153)